First Period:

Following last week's study of tech developments in the First World War, today we looked into some battles that used these new methods of warfare and the addition of chemical warfare. The Battle of Verdun began February 21, 1916 and ended December 18, 1916. This offensive was mounted by the Germans under General von Falkenhayn, and it took several months for the Allies to counterattack, which happened October 24, 1916, by the French. This battle was also the first incident of air-to-air combat with the Nieuport 17 aircraft equipped with rockets. On May 22, 1916, five of six German balloons were shot down by the French over the battlefields around Verdun. The destruction of the Verdun sector was devastating, as this was the first massive offensive as a "war of attrition." This term is used frequently to describe the battles of WWI, especially in regards to Verdun, and is defined as a "...steady erosion. As you wear down the other side they will hopefully realize that they are slowly being annihilated and will eventually capitulate... The goal of this strategy is that repeated defeat, even on a small scale, should lead the enemy to forecast eventual total loss and so submit. However the sting of defeat and the cost of capitulation may be such that commanders fight on to the very end. Against this, troops who also realize the inevitable may mutiny, desert or fight without spirit and so accelerate their doom... This can easily lead to a Pyrrhic victory where the cost to the victor leaves little to celebrate."(http://changingminds.org/disciplines/warfare/strategies/attrition.htm)

Bonus material on this battle, a 48 minute documentary: The Battle of Verdun, providing additional information on Fort Douaumont and a point by point explanation of the lead up to battle and the ensuing months of battle.

A few months later, the Battle of the Somme began on June 24, 1916, and ended on November 18, 1916. Epic History: WWI: Battle of the Somme was used in class. The casualties on the first few days of this battle were astronomical and very little was accomplished. German casualties: 12,000. French casualties: 7,000. British casualties: 57,000, the bloodiest day the British military had ever seen in its history. In nearly five months of battle, total casualties are difficult to fathom. German: 450,000. French: 200,000. British: 430,000.

Bonus material on this battle, a 51 minute documentary: Instruments of Death: Season 1, Episode 4-- The Somme 1916, providing information on trench warfare in this battle, infantry weapons, and tactics that did not utilize or recognize that this was a different war and the methods needed to match the technological advancements on the battlefield. Other bonus material is footage from the Battle of the Somme.

Trench warfare has been touched on several times in this study. These videos offer an explanation and diagrams on how trenches were built, used, and how deadly they would become. Trench Systems (Cross Section) and What Was Life Like in the Trenches of World War I? In conjunction with trench study, Weird Weapons and Equipment of WWI shows the makeshift weapons of men in the trenches.

For men in the trenches, the greatest threat and fear was gas, the newest advancement in warfare technology. The Father of Poison Gas--Fritz Haber (bonus material), was a German scientist who believed in the future of chemical warfare. His first wife was a chemist, and upon realizing what Haber was attempting and how it would effect the war effort, shot herself in the head. Later on, after the war was over, he continued his work in Germany until the Nazis came to power at which point they removed him from their employ for being a Jew, regardless of being Christianized. He moved to Britain, believing he would have a job. His innovations in chemical warfare, unsurprisingly did not garner him acceptance in Great Britain. Haber's work in chemicals and their use in war paved the path to Zyklon B, the gas used by the Nazis in death chambers and death camps like Auschwitz. Four different gases were invented for use in the First World War: tear gas, chlorine, phosgene/diphosgene, and mustard gas. Their affects and use in battle are documented in Poison Gas Warfare in WWI.

It's hard to imagine an area of land completely devastated by war. These weren't just battle fields. The names of these battles were primarily towns where people lived and went their way until the front came to them. Many times, the small villages were ravaged beyond recognition and have been left to grow over. Yet even after 100 years, the scars of war are still very much evident. The Destroyed Villages of France-Fleury walks through the remains of the village of Fleury, a village near Fort Douaumont and Verdun.

Several times over the course of this study, it has been made known that generals were woefully out of date, that expectations rarely fit the reality, and the age of the servicemen. For many who served, they were well under the 18-19 year old requirement. They were boys and on the frontlines. Britain's 250,000 boy soldiers in World War I is a 50 minute bonus video.

One last mention for this first period were the Pals Battalions, Heroes of WWI: Britain's Stock Broker Battalion, men who were encouraged to enlist together so they could fight alongside one another and not be placed in a battalion where they know no one. At first this seemed like a fantastic idea, especially when men joined up with friends and fellow tradesmen; i.e. all the bakers, or butchers, or bankers, etc. joined up together and serve. As the war trudged on past the "done by Christmas" slogan, and the horrors of war worsened, whole generations of men from single villages were wiped out along with their talents in the community of village life.

Second Period:

Tolkien wrote about the Siege of Gondor and the captain, and it's not too big of stretch to see it in terms of the Battle of the Somme. "Yet their Captain cared not greatly what they did or how many might be slain: their purpose was only to test the strength of the defense and to keep the men of Gondor busy in many places. All before the walls on either side of the Gate the ground was choked with wreck and with bodies of the slain; yet still driven as by a madness more and more came up." (Loconte, 73)

Years later, Blackadder took the generals of the First World War to task in clips from Advanced World War I Tactics with General Melchett. Bonus video by The Great War on Youtube: How Accurate is Blackadder Goes Forth? While not necessarily ALL true, there is a kernel of truth to the madness of tactics.

We moved on to Chapter Three of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War by Joseph Loconte. Most pertinent details of this chapter are on the battles of the Somme and trench warfare, covered in the first period. Given this, it makes sense for the chapter name to be "In a Hole in the Ground There Lived a Hobbit." Tolkien had a firm belief in the greatness that the little people can aspire to. In cases where the frontline soldiers were low ranking or mere boys, there is the greatest sense of heroics as they performed their duties in ghastly environments and little hope for survival. "As bad as the water, mud, rats, roaches, and lice was the smell: the stench of decaying flesh, human an animal, seemed to cover everything. Snipers, grenades, random shell fire, untreated wounds, disease-- any number of causes made death, and the smell of death, a constant presence for soldiers on the front line. Writes historian John Keegan: 'You could smell the front line miles before you could see it.'" (page 59) It puts to mind Pippin's song before Lord Denethor in Minas Tirith.

Ypres, Belgium saw chemical warfare up close for the first time on a large scale. Along the relatively straight trench line, running north/south in France, Germany, and Belgium, had bulges in some places. This bulge is called a salient. For this area, it was known as the Ypres Salient. Ypres: the Gas Inferno, a 43 minute documentary on the battles at Ypres and the use of gas, was shown in class, but only the first fifteen minutes or so. There were five battles around Ypres, and its decimation was immense. A French scout shot aerial footage of the destruction in 1919. These weren't just battle fields. They were cities. And nothing remained in the aftermath. Unlike Fleury, after the war, the people of Ypres returned and rebuilt the city in its original form. The West Yorkshire Regiment served at Ypres, and this link documents the battlefields of the area (Flanders Fields) and shows the rebuilt Ypres. There is an exceptional amount of footage of the battlefields and the men involved in the conflict.

One of the Battles of Ypres was at Passchendaele. Here are four links that detail the battle and why it was important to Ypres: Preparing for Battle, The First Day, Struggling in Mud, and A New Approach. Bonus material for Passchendaele is the 47 minute documentary The Battle of Passchendaele (100th Anniversary).

Also at the Battle of Ypres was Corporal Adolf Hitler, and his experiences in the First War influenced the rest of his life.

Thursday, September 27, 2018

Tuesday, September 25, 2018

Modern Euro, Week 3, Tech Developments in Warfare

We jumped into week three with a focus on technological advancements and mechanized warfare in the first period. As we've covered fairly extensively in the first two weeks, technology changed the methods by which war was conducted. You cannot teach or study the First World War and not focus on the drastic shift in how war was waged. European countries were wrapped up in their glory, and warfare was a noble endeavor. The generals of this era had virtually zero practical experience; the last skirmishes or wars, such as the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, were fought quickly and with the fanfare of the previous generation. The onset of World War I was a New War with Old Generals, as this video points out. The old methods could not compete with the new technologies and science advancements in killing. Tech Developments of World War I, a snippet of a video, begins by saying "Soldiers rode in on horses, and they left in airplanes." The greatest example of this is the cavalry. Between Tradition and Machine Guns details the shift from leading with cavalry first to their usage falling to the side. The cavalry was for charging against an enemy equally equipped and armed on horseback with sabres, and not machine guns.

In the movie War Horse, Steven Spielberg created a scene that illustrated the expectation versus the reality of this new war. (On a side note, there are some girls in my class that adore Benedict Cumberbatch and Tom Hiddleston. I've waited months to use this clip. The fallout was epic when they realized they died in the scene. I've been labeled evil... and I've been excessively amused all day thinking about it.)

In the movie War Horse, Steven Spielberg created a scene that illustrated the expectation versus the reality of this new war. (On a side note, there are some girls in my class that adore Benedict Cumberbatch and Tom Hiddleston. I've waited months to use this clip. The fallout was epic when they realized they died in the scene. I've been labeled evil... and I've been excessively amused all day thinking about it.)

The greatest advancements were those made for air warfare. In the early days, most planes were used for scouting and reconnaissance. These planes first dropped steel darts, bricks, and grenades by hand upon their enemies as they flew over. On October 5, 1914, Louis Quenault, a French pilot, opened fire on German aircraft and claimed the first air-to-air kill in history. Zeppelins were also widely used to cross the English Channel and hand drop bombs. In World War One: A Very Peculiar History, page 92 goes into more detail on these instances. As London was bombed by Zeppelins, the book states " Despite the danger, there were no air-raid sirens in London as it was thought they would cause panic!" This becomes a very different story during WWII.

For more information on aircraft and air warfare of World War I, the videos we viewed in class are:

Bonus material not used in class: Fight for Air Supremacy: Bloody April 1917 and World War I Uncut 8: Combat in the Skies.

The first period ended with a bit of pop culture: Snoopy vs. The Red Baron "Christmas Bells"

Second Period covered Chapter Two of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and The Great War by Joseph Loconte. The emphasis of this chapter was "duty, patriotism, and muscular religion." Page 30 says "Christianity and love of England went hand in hand, but the emphasis was on duty-- duty to king and country-- not on belief." A few pages later, the British applied the value of this war being a "Christian duty," "the belief that their nations were specially chosen by Providence to accomplish his progressive purposes on the world stage. Fidelity to God demanded fidelity to one's country as God's instrument, especially in wartime." (page 36) All facets of society encouraged this train of thought, and British men were shipped off, believing the God was on their side, they would squash those that were enemies, and do so quickly. Every nation involved in the war believed that what they were fighting was a holy war, like from the days of the Crusades, and fully expected to go do their job and be home by Christmas, as we discussed last week.

Arming British men with these beliefs, the men were woefully unprepared for the reality of what they experience on the front lines. Page 31 talks about Tolkien's experiences "...the 'universal weariness' of war and the 'bitter disillusionment' of discovering that his military training had not prepared him for the conditions of actual combat." Tolkien's biographer, Humphrey Carpenter, says in J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography " For signalers such as Tolkien there was a bitter disillusionment, as instead of the neat orderly conditions in which they had been trained they found a tangled confusion of wires, field telephones out of order and covered with mud, and worst of all a prohibition on the use of wires for all but the least important messages... Worst of all were the dead men, for corpses lay in every corner, horribly torn by shells. Those that still stared with dreadful eyes. Beyond the trenches no-man's-land was littered with bloated and decaying bodies. All around was desolation. Grass and corn vanished into a sea of mud. Trees, stripped of leaf and branch, stood as mere mutilated and blackened trunks. Tolkien never forgot what he called the 'animal horror' of trench warfare." (page 91)

Tolkien was one of four main founders of the Tea Club and Barrovian Society, an unofficial gathering of young men, who met on a regular basis to talk about life and their writing projects. Of this group, all but one, Christopher Wiseman, perished in the war, deeply affecting Tolkien for the rest of his life.

For the biggest chunk of time in the class, we viewed The Appendices Part 5: The War of the Ring, J.R.R. Tolkien: The Legacy of Middle Earth, this is from the third disc in the Return of the King, extended edition. It has some extraneous information, like Tolkien's love of languages and the creation of Quenya and Sindarin, but it goes into detail on how "the nobility of warfare no longer exists," the decisions a person makes to choose despair or to choose hope, and Tolkien's coined term "eucatastrophe," the opposite of catastrophe.

Bonus material for this period is a radio interview with Joseph Loconte and his book, also covering large chunks of the theme of the book, the first couple of chapters, and Tolkien's 'eucatastrophe.' I had initially intended this for use in class, but the clip is 38 minutes long, and not conducive to an enjoyable class experience.

Week four we will be going over the battles of Verdun and the Somme, trench warfare, and chemical warfare.

Thursday, September 13, 2018

Modern Euro: Week 2, War Begins and Eugenics

First Period:

In the years leading up to the war, the European powers-- namely Great Britain, Germany, and Russia-- believed two things: 1) the concept of "perpetual peace"; the idea that progress had allowed societies of the world so enlightened that they had reached an end to wars, and 2) industrialization and modernization endeavors would extend to protecting and growing their interests, hopefully done by rational means, but backed up with the creation of new technologies in warfare and the mobilization of massive armies. This was the zeitgeist-- the "spirit of the age"-- that defined the views of their world. As we study history we can't do so through the lens in how we perceive the world. However horrified or boggled by how they viewed the world, we cannot apply our understanding of it to how they understood it to work.

This pseudo-peace they believed possible cannot have realistically lasted long. Their rational minds deemed it so, but it doesn't take much for one country to look next door, see the military advancements and growing armies, and maintain that belief in the idea that war was going by the wayside. There was a greater tendency to be suspicious of neighboring countries, and often these suspicions were exploited by the respective governments to gain approval and support in their national endeavors, namely the mobilization of armies via conscription (compulsory military service). After the German army defeated the French in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, the rest of Europe realized Germany was successful in large part to their conscripted army, and jumped on board, beginning with the French who had no interest in sharing a border with Germany they couldn't protect. Great Britain did not change their stance on conscription and did not utilize it, mainly because Great Britain is an island and has no need for a large land army. The British navy was more than enough.

Add to this zeitgeist of progress and enlightenment the theory of evolution from Charles Darwin and his On the Origin of the Species of 1859. This seems like it wouldn't have much to do with the evolving (couldn't resist that) ideas of what industrialization and modernization had achieved for the world. Moving along the timeline a few years, Herbert Spencer, a British philosopher and biologist, wrote Principles of Biology in 1864 and coined the phrase "survival of the fittest" as he expounded on Darwin's theory of evolution and applied it to society. Spencer thought this Social Darwinism could categorize humans in much the same way as every other organism in the world and assign it value.

As each country of the late 1800s pressed forward with these new theories, their suspicions were given credence. It seemed reasonable to vilify the 'others' in society. In Great Britain in 1887, it was easy to encourage people to by British products simply by putting a "Made in Germany" label on imported items. As the years passed and tensions grew ever more taut, the theme stayed the same: British, good, and German, bad; going so far as to renaming dog breeds (German Shepherds to Alsatians) and even some Britains killing their pets because they were called Dachshunds, reflecting a deepening angst against Germany (Great Britain's greatest threat). On the flip side, as World War I: A Very Peculiar History puts it "All bars, shops, and hotels with English or French names were renamed," and even the French tried to "rename the perfume eau de Cologne (named after a German town) to eau de Provence (after a French region)." On the same token, the United States didn't kill their Dachshunds, they just renamed them 'liberty dogs'. Many libraries in the US also held public book burnings of German material.

The question of how did European countries get involved in the First World War was covered briefly last week and was largely explained by the ideals of nationalism and the alliance systems in place. June 1914 was reported to be the loveliest of summers, most countries reveling in their modernity and what progress had done for them. This feeling was short lived. Europe was a Tinderbox waiting for a spark to justify war. Then, on June 28, 1914, the spark-- the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife-- burned, igniting the countries of Europe into war in just a few weeks. John Green and Crash Course History delve into who actually started the war (which will be important to the end of this semester and the Treaty of Versailles). For more information on the How Europe Spiraled into War, check out this video.

Great Britain, France, Russia, and Germany all believed their nations to be unstoppable, at the top of their game. The expectation for this war was "It will be over by Christmas!" If war was conducted as it had been in previous generations, then, yes, this war of only a few months would be plausible, but the generals and armies were grossly unprepared to deal with the old style of warfare juxtaposed with the new technology. As the first few months dragged on, the hope of making it back home in time for Christmas dwindled. In a moment of good will on the battlefield, the guns went silent and an unofficial "Christmas Truce" was declared in No Man's Land, the stretch of land between the trenches.

Readings for this first period are from World War I: A Very Peculiar History, pages 6-10, 33-37, 38-45, and 48-51

Second Period:

We started the conversation about Darwin and Social Darwinism in the last class. Of all the theories and philosophies of the time, these two would have unfathomable consequences for humanity. When talking about genocide of the atrocities that took place in the first half of the last century, it is often most laid neatly at the doorstep of Germany. This is a white washing of history-- a sloppy paint job to quickly hide the unsavory details of eugenics. Last week we saw a video about Cecil Rhodes, his attitudes toward 'lower societies,' and his own scramble for Africa in the creation of his own African country, aptly named Rhodesia. Racism in Victorian England is a fantastic lecture (and unfortunately not viewed in today's class) given by Richard J. Evans, a learned historian in the field of 19th and 20th century history, with an interest in Germany. You simply cannot study this field and not run into his name whether in lectures or his many books on the subjects. This specific lecture details British attitudes toward race.

In the years leading up to the war, the European powers-- namely Great Britain, Germany, and Russia-- believed two things: 1) the concept of "perpetual peace"; the idea that progress had allowed societies of the world so enlightened that they had reached an end to wars, and 2) industrialization and modernization endeavors would extend to protecting and growing their interests, hopefully done by rational means, but backed up with the creation of new technologies in warfare and the mobilization of massive armies. This was the zeitgeist-- the "spirit of the age"-- that defined the views of their world. As we study history we can't do so through the lens in how we perceive the world. However horrified or boggled by how they viewed the world, we cannot apply our understanding of it to how they understood it to work.

This pseudo-peace they believed possible cannot have realistically lasted long. Their rational minds deemed it so, but it doesn't take much for one country to look next door, see the military advancements and growing armies, and maintain that belief in the idea that war was going by the wayside. There was a greater tendency to be suspicious of neighboring countries, and often these suspicions were exploited by the respective governments to gain approval and support in their national endeavors, namely the mobilization of armies via conscription (compulsory military service). After the German army defeated the French in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, the rest of Europe realized Germany was successful in large part to their conscripted army, and jumped on board, beginning with the French who had no interest in sharing a border with Germany they couldn't protect. Great Britain did not change their stance on conscription and did not utilize it, mainly because Great Britain is an island and has no need for a large land army. The British navy was more than enough.

Add to this zeitgeist of progress and enlightenment the theory of evolution from Charles Darwin and his On the Origin of the Species of 1859. This seems like it wouldn't have much to do with the evolving (couldn't resist that) ideas of what industrialization and modernization had achieved for the world. Moving along the timeline a few years, Herbert Spencer, a British philosopher and biologist, wrote Principles of Biology in 1864 and coined the phrase "survival of the fittest" as he expounded on Darwin's theory of evolution and applied it to society. Spencer thought this Social Darwinism could categorize humans in much the same way as every other organism in the world and assign it value.

As each country of the late 1800s pressed forward with these new theories, their suspicions were given credence. It seemed reasonable to vilify the 'others' in society. In Great Britain in 1887, it was easy to encourage people to by British products simply by putting a "Made in Germany" label on imported items. As the years passed and tensions grew ever more taut, the theme stayed the same: British, good, and German, bad; going so far as to renaming dog breeds (German Shepherds to Alsatians) and even some Britains killing their pets because they were called Dachshunds, reflecting a deepening angst against Germany (Great Britain's greatest threat). On the flip side, as World War I: A Very Peculiar History puts it "All bars, shops, and hotels with English or French names were renamed," and even the French tried to "rename the perfume eau de Cologne (named after a German town) to eau de Provence (after a French region)." On the same token, the United States didn't kill their Dachshunds, they just renamed them 'liberty dogs'. Many libraries in the US also held public book burnings of German material.

The question of how did European countries get involved in the First World War was covered briefly last week and was largely explained by the ideals of nationalism and the alliance systems in place. June 1914 was reported to be the loveliest of summers, most countries reveling in their modernity and what progress had done for them. This feeling was short lived. Europe was a Tinderbox waiting for a spark to justify war. Then, on June 28, 1914, the spark-- the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife-- burned, igniting the countries of Europe into war in just a few weeks. John Green and Crash Course History delve into who actually started the war (which will be important to the end of this semester and the Treaty of Versailles). For more information on the How Europe Spiraled into War, check out this video.

Great Britain, France, Russia, and Germany all believed their nations to be unstoppable, at the top of their game. The expectation for this war was "It will be over by Christmas!" If war was conducted as it had been in previous generations, then, yes, this war of only a few months would be plausible, but the generals and armies were grossly unprepared to deal with the old style of warfare juxtaposed with the new technology. As the first few months dragged on, the hope of making it back home in time for Christmas dwindled. In a moment of good will on the battlefield, the guns went silent and an unofficial "Christmas Truce" was declared in No Man's Land, the stretch of land between the trenches.

Readings for this first period are from World War I: A Very Peculiar History, pages 6-10, 33-37, 38-45, and 48-51

Second Period:

We started the conversation about Darwin and Social Darwinism in the last class. Of all the theories and philosophies of the time, these two would have unfathomable consequences for humanity. When talking about genocide of the atrocities that took place in the first half of the last century, it is often most laid neatly at the doorstep of Germany. This is a white washing of history-- a sloppy paint job to quickly hide the unsavory details of eugenics. Last week we saw a video about Cecil Rhodes, his attitudes toward 'lower societies,' and his own scramble for Africa in the creation of his own African country, aptly named Rhodesia. Racism in Victorian England is a fantastic lecture (and unfortunately not viewed in today's class) given by Richard J. Evans, a learned historian in the field of 19th and 20th century history, with an interest in Germany. You simply cannot study this field and not run into his name whether in lectures or his many books on the subjects. This specific lecture details British attitudes toward race.

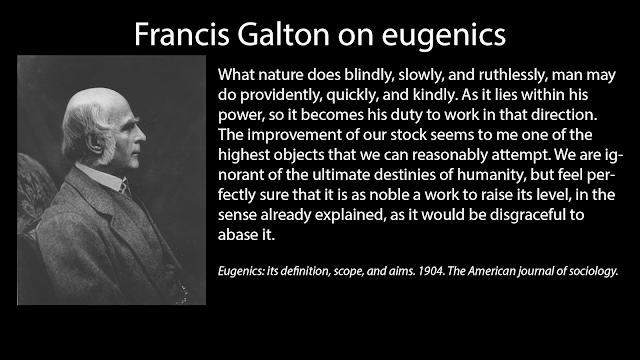

The ideology of eugenics was perpetuated throughout Great Britain and the United States. The Unites States had the first eugenics laws on the books; the forced sterilization of what they determined to be 'imbeciles.'

This was not just a few people pushing an agenda, it was widely supported and accepted by the wealthy, the intellectuals, and men with governmental power: the likes of W.E.B DuBois, Alexander Graham Bell, Henry Ford, David Starr Jordan (president of Stanford), Margaret Sanger, Upton Sinclair, President Calvin Coolidge, members of the Kellogg family, and the foundations of Carnegie and Rockefeller (who specifically aided German eugenics programs under the Nazis, including the sadistic interests of Josef Mengele at Auschwitz).

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., Supreme Court Justice, wrote the decision for Buck vs. Bell, a case concerning the compulsory sterilization of Carrie Buck, a woman deemed an 'imbecile' in Virginia. His words are as follows: It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind... Three generations of imbeciles are enough."

In the Joseph Loconte book, A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War, page 20-21, the statements are made: "It's important to remember that eugenicists thought themselves as reformers, committed to improving the human condition. They endorsed the idea of state action to achieve their goals... they emphasized the collective destiny of the human race, at the expense of the individual. The conceit of the intellectual elites of the day was that science, and the technology it underwrites, could solve the most intractable of human problems." Sounds a bit Karl Marx to me, also another German philosopher throwing a wrench into the world's zeitgeist at the time. Tolkien and Lewis both were horrified at this view of humanity, and again on the same pages of Loconte's book, the two men wrote their works with "a vital theme throughout is the sacred worth of the individual soul; in Middle Earth and in Narnia, every life is of immense consequence."

Charles Darwin, Herbert Spencer, Karl Marx, and Friedrich Nietzche ('God is dead' dude) developed theories to explain away the dignity of human beings as just beings that exist like any other organism and can be put into a category to do with them whatever was necessary to the benefit of all. In this clip, we see the consequences fo out of control industrialization, the destruction of nature, and the genetic engineering of a master race from the viewpoint of Tolkien.

This was 'progress' and the intellectuals believed that human society had categories, based on a myriad of things, but the lofty top was conveniently populated by the same intellectual elite that theorized this all.

Their zeitgeist was knowing they had reached the pinnacle of rational thought and in terms of war, there was what Immanuel Kant (German philosopher, 1724-1804) described as "perpetual peace." This idea that the masters of Europe were rational and enlightened enough, to eschew war. Loconte quotes H.G. Wells on page 4, "I think that in decades before 1914 not only I but most of my generation-- in the British Empire, America, France, and indeed throughout most of the civilized world-- thought that war was dying out. So it seemed to us." War was no longer en vogue, no matter what technological advancements had made or the growing number of mobilized troops.

All these theories came together in a gloppy soup of Darwinism, Social Darwinism, Industrialization, Technology and Modernization, Marxism, and Nationalism (a "political, social, and economic system characterized by the promotion of the interests of a particular nation, especially with the aim of gaining and maintaining sovereignty (self-governance) over the homeland," Wikipedia). But how does this affect every one else not in the upper echelons of society or the intellectuals? How do you convince someone how to think a certain way on a subject? Propaganda. The easiest way to convince the masses that there are divisions between nations, that one nation is better, that their nation is better, and if/when war breaks out, it will be up to the people to maintain their beliefs and fight for the nation.

For the first time, movies could bring war zones to life. Film, in its youngest days, could be use to influence and describe the war.

Readings for the second period were from A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War, Introduction and Chapter One.

Thursday, September 6, 2018

Modern Euro: Week 1, Industrialization and Imperialism

*This class is two periods long and will be notated at the appropriate moments in the blog for the students.

First Period:

The idea for this class began as a request for a study of the Holocaust. As this is an eight week course, I struggled with covering the material in such a short span of time that would do the topic any sort of justice. When thinking of historical events and how to teach them, I start with the question: Where to start? You don't get to Hitler, World War II, and the Holocaust by thinking Hitler woke up one day as an antisemitic megalomaniac intent on the destruction of all of all but the Aryan race. His views were set firmly in the history of his experiences, specifically his role in the first world war. But then to understand those experiences, we must study World War I to understand why the experiences of this war led the next war. So why did the first war happen? What was the global worldview? What were the views of the nation states involved? Where were these nations (Great Britain, France, Russia, and Germany) in their specifics histories? How did the world, seemingly peaceful at the time, explode into total war? This eight week course suddenly became a two semester, 16 week course, as I tried to answer my own question of where to start.

The answer is 1850. That's were we start. It's a bit of a random date and not based off of any real event. This age was progress and modernization. It was the age of industrialization and imperialism, two major factors in the lead up to the first world war and how destructive this war would be remembered for. Great Britain was the mother of industrialization. What is industrialization? Coal, Steam, and the Industrial Revolution: Crash Course World History is best summation I've found. And it's John Green. A double win.

Industrialization and Great Britain as a global leader lead to the Great Exhibition in London, 1851. Britain, as host of this event, was determined to show off her industries. The building itself was built of steel and glass, two unheard of building materials until this time. The Great Exhibition of 1851 was proof to the world that Great Britain was all things shiny and new; they were enlightened, and leading the future as never before seen in the history of all time past.

First Period:

The idea for this class began as a request for a study of the Holocaust. As this is an eight week course, I struggled with covering the material in such a short span of time that would do the topic any sort of justice. When thinking of historical events and how to teach them, I start with the question: Where to start? You don't get to Hitler, World War II, and the Holocaust by thinking Hitler woke up one day as an antisemitic megalomaniac intent on the destruction of all of all but the Aryan race. His views were set firmly in the history of his experiences, specifically his role in the first world war. But then to understand those experiences, we must study World War I to understand why the experiences of this war led the next war. So why did the first war happen? What was the global worldview? What were the views of the nation states involved? Where were these nations (Great Britain, France, Russia, and Germany) in their specifics histories? How did the world, seemingly peaceful at the time, explode into total war? This eight week course suddenly became a two semester, 16 week course, as I tried to answer my own question of where to start.

The answer is 1850. That's were we start. It's a bit of a random date and not based off of any real event. This age was progress and modernization. It was the age of industrialization and imperialism, two major factors in the lead up to the first world war and how destructive this war would be remembered for. Great Britain was the mother of industrialization. What is industrialization? Coal, Steam, and the Industrial Revolution: Crash Course World History is best summation I've found. And it's John Green. A double win.

Industrialization and Great Britain as a global leader lead to the Great Exhibition in London, 1851. Britain, as host of this event, was determined to show off her industries. The building itself was built of steel and glass, two unheard of building materials until this time. The Great Exhibition of 1851 was proof to the world that Great Britain was all things shiny and new; they were enlightened, and leading the future as never before seen in the history of all time past.

Yay for Great Britain. That wonder of modernization. The first to industrialize and lead the globe to a modernized world. While much was made of the wonders of world at the Great Exhibition (think Around the World in 80 Days by Jules Verne and the 2004 movie with Steve Coogan and Jackie Chan), there was the seedier side of industrialization; the poor conditions, child labor, destitution, the growing division between the social classes and their financial statuses that were expressed in the works of Charles Dickens: Oliver Twist (1838), A Christmas Carol (1843), David Copperfield (1850), Bleak House (1853), Hard Times (1854), Little Dorrit (1855), Great Expectations (1861), and others that crafted the life of Great Britain, from its illustriousness to the sordid. (This video gives more information on Charles Dickens and how his writing made an impact on British society and politics.)

British industrialization spurred on other nations in a race to modernize, but these nations did so at a much slower pace. The Turkish Ottoman Empire resisted modernization and was labeled the "sick man of Europe." This resistance eventually led to its downfall (from 1908-1922) as they met armies with technological advancements. France plodded slowly on, and the nation-state of Germany was non-existent until 1871, exceptionally late to the game of governance and industrialization in Europe.

The unification of Germany in 1871 was the culmination of the rapid rise of Prussia and the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 which saw Prussia as the victor and the glue that put the nation-state of Germany together. It also irritated the French just enough to hold a grudge for a few decades when France ceded Alsace-Lorraine to Germany for having lost that war. Later on, you will see the French have a long memory and made sure Alsace-Lorraine did not stay a German province.

In this video, Europe Prior to World War I: Alliances and Enemies (tiny note here: for younger audiences, he uses one word that can be muted at 4:39), Indiana Nidell (get used to watching his videos because he has a wealth of information to offer in his The Great War series) details the struggle for global power among European nations many technological advancements at a time and a brief bit on the alliance system in place across Europe that put the nations in place for war. Germany (Berlin, specifically) was the cultural center of Europe and its industries had finally surpassed the abilities of Great Britain. The problem came from the precarious, sometimes non-active governance of Austro-Hungary. The Slavic countries, the Ottomans, and the the area of the Balkans were accustomed to unrest, and most of Europe and Russia kept tabs on the upheaval, generally brushing the Balkan issues of as regular occurrences and not something to worry too much about. This video, not used in today's class, but a nice extra tidbit gives details on the frequent problems of the Balkans leading up to the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the tinderbox that brought the First World War. Not much attention will be given to the Ottoman or African fronts of the First War period, as the focus in primarily Europe.

Second Period:

For industrialized nations like Great Britain, the need for raw materials grew as rapidly as production. Falling back on their age old colonial standard, Great Britain utilized their brand of imperialism to expand their business of power. John Green's Crash Course: Imperialism video states "Industrialized nations push economic integration upon developing nations, and then extract value from those developing nations, just as you would from a mine or a field owned." As other nations began their journey toward modernization, they followed the pattern set forth by Great Britain: industrialization then imperialism.

According to wikipedia, imperialism is "a policy that involves a nation extending its power by the acquisition of lands by purchase, diplomacy, or military force. This new era of technology and enlightened thinking (think back to John Green's questioning of Eurocentrism), conquest of lesser nations was a right. Germany had industrialized and modernized, and now needed something to flex its muscle and gain territory. Berlin's status in Europe had gained substantial influence in the few years from the Unification (1871) to 1884, when a European get-together was called. The Berlin Conference of 1884 set off the "Scramble for Africa," the partitioning of African territories to be colonized by European countries. This period of colonization was known as New Imperialism.

For this second period, the text we will be using is A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War by Joseph Loconte. I always set out to utilize some form of literature from whatever time period I'm studying/teaching. Using the works of people who lived during a given period of time brings the story and the struggle of that history to something be something real, tangible, and relatable. The literature that proceeds from this particular era can be such a drudgery. I could't do that. So we have this lovely selection that details the experiences, lives, and friendship of J.R.R. Tolkien (brief biography from The Great War here) and C.S. Lewis and their use of fiction and myth to find a way to make sense of the World War I. In November, this book will be airing as a five part documentary in remembrance of Armistice Day (the end of the war) 100 years ago. The trailer for that is here and well worth watching.

As today's lesson was primarily on industrialization and modernization, it may seem a bizarre way to begin studying the First World War. However, it is everything that made the war unlike any war the world had ever seen. Where technology and machines have little concern for life or the world around us. J.R.R Tolkien and C.S. Lewis were acutely aware of how industry changes a landscape. They watched their idyllic, English countryside fill with factories, rapid urbanization, the destruction of the natural environment, and recognized that even in the face of "progress" there was an evil that came with it. If you have seen The Lord of Rings Trilogy, you will recall instances where Tolkien mourned the desolation left in the wake of progress. He specifically uses Treebeard and the Ents. As we wrap up the first lesson, here are three links to scenes from The Two Towers, that when watched from the view of the downside of industrialization and technology, take on more meaning than just a bit of entertainment.

*Next week is the Alliance System, the outbreak of war, and the first few months for first period. The second period delves into Social Darwinism, Eugenics, and propaganda.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)